Nitro-bid

(Nitroglycerin)Nitro-Bid Prescribing Information

Nitroglycerin ointment is indicated for the prevention of angina pectoris due to coronary artery disease. The onset of action of transdermal nitroglycerin is not sufficiently rapid for this product to be useful in aborting an acute anginal episode.

As noted above

The principal pharmacological action of nitroglycerin is relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and consequent dilatation of peripheral arteries and veins, especially the latter. Dilatation of the veins promotes peripheral pooling of blood and decreases venous return to the heart, thereby reducing left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (preload). Arteriolar relaxation reduces systemic vascular resistance, systolic arterial pressure, and mean arterial pressure (afterload). Dilatation of the coronary arteries also occurs. The relative importance of preload reduction, afterload reduction, and coronary dilatation remains undefined.

Dosing regimens for most chronically used drugs are designed to provide plasma concentrations that are continuously greater than a minimally effective concentration. This strategy is inappropriate for organic nitrates. Several well-controlled clinical trials have used exercise testing to assess the anti-anginal efficacy of continuously-delivered nitrates. In the large majority of these trials, active agents were indistinguishable from placebo after 24 hours (or less) of continuous therapy. Attempts to overcome nitrate tolerance by dose escalation, even to doses far in excess of those used acutely, have consistently failed. Only after nitrates had been absent from the body for several hours was their anti-anginal efficacy restored.

The first products in the metabolism of nitroglycerin are inorganic nitrate and the 1,2- and 1,3-dinitroglycerols. The dinitrates are less effective vasodilators than nitroglycerin, but they are longer-lived in the serum, and their net contribution to the overall effect of chronic nitroglycerin regimens is not known. The dinitrates are further metabolized to (non-vasoactive) mononitrates and, ultimately, to glycerol and carbon dioxide.

To avoid development of tolerance to nitroglycerin, drug-free intervals of 10 - 12 hours are known to be sufficient; shorter intervals have not been well studied. In one well-controlled clinical trial, subjects receiving nitroglycerin appeared to exhibit a rebound or withdrawal effect, so that their exercise tolerance at the end of the daily drug-free interval was less than that exhibited by the parallel group receiving placebo.

Reliable assay techniques for plasma nitroglycerin levels have only recently become available, and studies using these techniques to define the pharmacokinetics of nitroglycerin ointment have not been reported. Published studies using older techniques provide results that often differ, in similar experimental settings, by an order of magnitude. The data are consistent, however, in suggesting that nitroglycerin levels rise to steady state within an hour or so of application of ointment, and that after removal of nitroglycerin ointment, levels wane with a half-life of about half an hour.

The onset of action of transdermal nitroglycerin is not sufficiently rapid for this product to be useful in aborting an acute anginal episode.

The maximal achievable daily duration of anti-anginal activity provided by nitroglycerin ointment therapy has not been studied. Recent studies of other formulations of nitroglycerin suggest that the maximal achievable daily duration of anti-anginal effect from nitroglycerin ointment will be about 12 hours.

It is reasonable to believe that the rate and extent of nitroglycerin absorption from ointment may vary with the site and square measure of the skin over which a given dose of ointment is spread, but these relationships have not been adequately studied.

In some controlled trials of other organic nitrate formulations, efficacy has declined with time. Because controlled, long-term trials of nitroglycerin ointment have not been reported, it is not known how the efficacy of nitroglycerin ointment may vary during extended therapy.

It is reasonable to believe that the rate and extent of nitroglycerin absorption from ointment may vary with the site and square measure of the skin over which a given dose of ointment is spread, but these relationships have not been adequately studied.

Controlled trials with other formulations of nitroglycerin have demonstrated that if plasma levels are maintained continuously, all anti-anginal efficacy is lost within 24 hours. This tolerance cannot be overcome by increasing the dose of nitroglycerin. As a result, any regimen of NITRO-BID® administration should include a daily nitrate-free interval. The minimum necessary length of such an interval has not been defined, but studies with other nitroglycerin formulations have shown that 10 to 12 hours is sufficient.

Thus, one appropriate dosing schedule for NITRO-BID® would begin with two daily 1/2- inch (7.5 mg) doses, one applied on rising in the morning and one applied six hours later. The dose could be doubled, and even doubled again, in patients tolerating this dose but failing to respond to it. The foilpac is intended as a unit dose package only and is equivalent to approximately 1 inch as squeezed from the tube. Use entire contents of foilpac to obtain full dose and discard immediately after use.

Each tube of ointment and each box of foilpacs is supplied with a pad of ruled, impermeable, paper applicators. These applicators allow ointment to be absorbed through a much smaller area of skin than that used in any of the reported clinical trials, and the significance of this difference is not known. To apply the ointment using one of the applicators, place the applicator on a flat surface, printed side down. Squeeze the necessary amount of ointment from the tube onto the applicator, place the applicator (ointment side down) on the desired area of the skin, and tape the applicator into place.

Allergic reactions to organic nitrates are extremely rare, but they do occur. Nitroglycerin is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to it.

Adverse reactions to nitroglycerin are generally dose-related, and almost all of these reactions are the result of nitroglycerin's activity as a vasodilator. Headache, which may be severe, is the most commonly reported side effect. Headache may be recurrent with each daily dose, especially at higher doses. Transient episodes of lightheadedness, occasionally related to blood pressure changes, may also occur. Hypotension occurs infrequently, but in some patients it may be severe enough to warrant discontinuation of therapy. Syncope, crescendo angina, and rebound hypertension have been reported but are uncommon.

Allergic reactions to nitroglycerin are also uncommon, and the great majority of those reported have been cases of contact dermatitis or fixed drug eruptions in patients receiving nitroglycerin in ointments or patches. There have been a few reports of genuine anaphylactoid reactions, and these reactions can probably occur in patients receiving nitroglycerin by any route.

Extremely rarely, ordinary doses of organic nitrates have caused methemoglobinemia in normal-seeming patients; for further discussion of its diagnosis and treatment see

Laboratory determinations of serum levels of nitroglycerin and its metabolites are not widely available, and such determinations have, in any event, no established role in the management of nitroglycerin overdose.

No data are available to suggest physiological maneuvers (e.g., maneuvers to change the pH of the urine) that might accelerate elimination of nitroglycerin and its active metabolites. Similarly, it is not known which—if any—of these substances can usefully be removed from the body by hemodialysis.

No specific antagonist to the vasodilator effects of nitroglycerin is known, and no intervention has been subject to controlled study as a therapy of nitroglycerin overdose. Because the hypotension associated with nitroglycerin overdose is the result of venodilatation and arterial hypovolemia, prudent therapy in this situation should be directed toward increase in central fluid volume. Passive elevation of the patient's legs may be sufficient, but intravenous infusion of normal saline or similar fluid may also be necessary.

The use of epinephrine or the arterial vasoconstrictors in this setting is likely to do more harm than good.

In patients with renal disease or congestive heart failure, therapy resulting in central volume expansion is not without hazard. Treatment of nitroglycerin overdose in these patients may be subtle and difficult, and invasive monitoring may be required.

Notwithstanding these observations, there are case reports of significant methemoglobinemia in association with moderate overdoses of organic nitrates. None of the affected patients had been thought to be unusually susceptible.

Methemoglobin levels are available from most clinical laboratories. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients who exhibit signs of impaired oxygen delivery despite adequate cardiac output and adequate arterial pO2. Classically, methemoglobinemic blood is described as chocolate brown, without color change on exposure to air.

When methemoglobinemia is diagnosed, the treatment of choice is methylene blue, 1-2 mg/kg intravenously.

Data are not available to allow estimation of the frequency of adverse reactions during treatment with nitroglycerin ointment.

Marked symptomatic orthostatic hypotension has been reported when calcium channel blockers and organic nitrates were used in combination. Dose adjustments of either class of agents may be necessary.

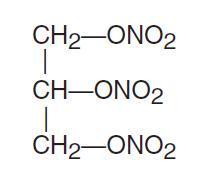

Nitroglycerin is 1,2,3-propanetriol trinitrate, an organic nitrate whose structural formula is:

and whose molecular weight is 227.09. The organic nitrates are vasodilators, active on both arteries and veins.

NITRO-BID® for topical use contains lactose and 2% nitroglycerin in a base of lanolin, white petrolatum and purified water. Each inch (2.5 cm), as squeezed from the tube, contains approximately 15 mg of nitroglycerin.