Propofol Injectable Emulsion

Propofol Injectable Emulsion Prescribing Information

Propofol injectable emulsion is an intravenous general anesthetic and sedation drug indicated for:

• Induction of General Anesthesia for Patients Greater than or Equal to 3 Years of Age

• Maintenance of General Anesthesia for Patients Greater than or Equal to 2 Months of Age

• Initiation and Maintenance of Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC) Sedation in Adult Patients

• Sedation for Adult Patients in Combination with Regional Anesthesia

• Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Sedation of Intubated, Mechanically Ventilated Adult Patients

Propofol injectable emulsion is not recommended for induction of anesthesia below the age of 3 years or for maintenance of anesthesia below the age of 2 months because its safety and effectiveness have not been established in those populations

The safety and effectiveness of propofol injectable emulsion have been established for induction of anesthesia in pediatric patients aged 3 years and older and for the maintenance of anesthesia aged 2 months and older.

In pediatric patients, administration of fentanyl concomitantly with propofol injectable emulsion may result in serious bradycardia

Propofol injectable emulsion is not indicated for use in pediatric patients for ICU sedation or for MAC sedation for surgical, nonsurgical or diagnostic procedures as safety and effectiveness have not been established.

There have been anecdotal reports of serious adverse events and death in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections receiving propofol injectable emulsion for ICU sedation.

In one multicenter clinical trial of ICU sedation in critically ill pediatric patients that excluded patients with upper respiratory tract infections, the incidence of mortality observed in patients who received propofol (n=222) was 9%, while that for patients who received standard sedative agents (n=105) was 4%. While causality was not established in this study, propofol is not indicated for ICU sedation in pediatric patients until further studies have been performed to document its safety in that population

In pediatric patients, abrupt discontinuation of propofol injectable emulsion following prolonged infusion may result in flushing of the hands and feet, agitation, tremulousness and hyperirritability. Increased incidences of bradycardia (5%), agitation (4%), and jitteriness (9%) have also been observed.

Benzyl alcohol, a component of this product, has been associated with serious adverse events and death, particularly in pediatric patients. The "gasping syndrome," (characterized by central nervous system depression, metabolic acidosis, gasping respirations, and high levels of benzyl alcohol and its metabolites found in the blood and urine) has been associated with benzyl alcohol dosages >99 mg/kg/day in neonates and low-birth weight neonates. Additional symptoms may include gradual neurological deterioration, seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, hematologic abnormalities, skin breakdown, hepatic and renal failure, hypotension, bradycardia, andcardiovascular collapse.

Although normal therapeutic doses of this product deliver amounts of benzyl alcohol that are substantially lower than those reported in association with the "gasping syndrome," the minimum amount of benzyl alcohol at which toxicity may occur is not known. Premature and low-birth weight infants, as well as patients receiving high dosages, may be more likely to develop toxicity. Practitioners administering this and other medications containing benzyl alcohol should consider the combined daily metabolic load of benzyl alcohol from all sources.

Published juvenile animal studies demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs, such as propofol, that either block NMDA receptors or potentiate the activity of GABA during the period of rapid brain growth or synaptogenesis, results in wide spread neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell loss in the developing brain and alterations in synaptic morphology and neurogenesis. Based on comparisons across species, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester of gestation through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately 3 years of age in humans.

In primates, exposure to 3 hours of ketamine that produced a light surgical plane of anesthesia did not increase neuronal cell loss, however, treatment regimens of 5 hours or longer of isoflurane increased neuronal cell loss. Data from isoflurane-treated rodents and ketamine-treated primates suggest that the neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell losses are associated with prolonged cognitive deficits in learning and memory. The clinical significance of these nonclinical findings is not known, and healthcare providers should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in pregnant women, neonates, and young children who require procedures with the potential risks suggested by the nonclinical data

Safety, effectiveness and dosing guidelines for propofol injectable emulsion have not been established for MAC sedation in the pediatric population; therefore, it is not recommended for this use

The safety and effectiveness of propofol injectable emulsion have been established for induction of anesthesia in pediatric patients aged 3 years and older and for the maintenance of anesthesia aged 2 months and older.

In pediatric patients, administration of fentanyl concomitantly with propofol injectable emulsion may result in serious bradycardia

Propofol injectable emulsion is not indicated for use in pediatric patients for ICU sedation or for MAC sedation for surgical, nonsurgical or diagnostic procedures as safety and effectiveness have not been established.

There have been anecdotal reports of serious adverse events and death in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections receiving propofol injectable emulsion for ICU sedation.

In one multicenter clinical trial of ICU sedation in critically ill pediatric patients that excluded patients with upper respiratory tract infections, the incidence of mortality observed in patients who received propofol (n=222) was 9%, while that for patients who received standard sedative agents (n=105) was 4%. While causality was not established in this study, propofol is not indicated for ICU sedation in pediatric patients until further studies have been performed to document its safety in that population

In pediatric patients, abrupt discontinuation of propofol injectable emulsion following prolonged infusion may result in flushing of the hands and feet, agitation, tremulousness and hyperirritability. Increased incidences of bradycardia (5%), agitation (4%), and jitteriness (9%) have also been observed.

Benzyl alcohol, a component of this product, has been associated with serious adverse events and death, particularly in pediatric patients. The "gasping syndrome," (characterized by central nervous system depression, metabolic acidosis, gasping respirations, and high levels of benzyl alcohol and its metabolites found in the blood and urine) has been associated with benzyl alcohol dosages >99 mg/kg/day in neonates and low-birth weight neonates. Additional symptoms may include gradual neurological deterioration, seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, hematologic abnormalities, skin breakdown, hepatic and renal failure, hypotension, bradycardia, andcardiovascular collapse.

Although normal therapeutic doses of this product deliver amounts of benzyl alcohol that are substantially lower than those reported in association with the "gasping syndrome," the minimum amount of benzyl alcohol at which toxicity may occur is not known. Premature and low-birth weight infants, as well as patients receiving high dosages, may be more likely to develop toxicity. Practitioners administering this and other medications containing benzyl alcohol should consider the combined daily metabolic load of benzyl alcohol from all sources.

Published juvenile animal studies demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs, such as propofol, that either block NMDA receptors or potentiate the activity of GABA during the period of rapid brain growth or synaptogenesis, results in wide spread neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell loss in the developing brain and alterations in synaptic morphology and neurogenesis. Based on comparisons across species, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester of gestation through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately 3 years of age in humans.

In primates, exposure to 3 hours of ketamine that produced a light surgical plane of anesthesia did not increase neuronal cell loss, however, treatment regimens of 5 hours or longer of isoflurane increased neuronal cell loss. Data from isoflurane-treated rodents and ketamine-treated primates suggest that the neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell losses are associated with prolonged cognitive deficits in learning and memory. The clinical significance of these nonclinical findings is not known, and healthcare providers should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in pregnant women, neonates, and young children who require procedures with the potential risks suggested by the nonclinical data

Propofol injectable emulsion is not indicated for use in Pediatric ICU sedation since the safety of this regimen has not been established

The safety and effectiveness of propofol injectable emulsion have been established for induction of anesthesia in pediatric patients aged 3 years and older and for the maintenance of anesthesia aged 2 months and older.

In pediatric patients, administration of fentanyl concomitantly with propofol injectable emulsion may result in serious bradycardia

Propofol injectable emulsion is not indicated for use in pediatric patients for ICU sedation or for MAC sedation for surgical, nonsurgical or diagnostic procedures as safety and effectiveness have not been established.

There have been anecdotal reports of serious adverse events and death in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections receiving propofol injectable emulsion for ICU sedation.

In one multicenter clinical trial of ICU sedation in critically ill pediatric patients that excluded patients with upper respiratory tract infections, the incidence of mortality observed in patients who received propofol (n=222) was 9%, while that for patients who received standard sedative agents (n=105) was 4%. While causality was not established in this study, propofol is not indicated for ICU sedation in pediatric patients until further studies have been performed to document its safety in that population

In pediatric patients, abrupt discontinuation of propofol injectable emulsion following prolonged infusion may result in flushing of the hands and feet, agitation, tremulousness and hyperirritability. Increased incidences of bradycardia (5%), agitation (4%), and jitteriness (9%) have also been observed.

Benzyl alcohol, a component of this product, has been associated with serious adverse events and death, particularly in pediatric patients. The "gasping syndrome," (characterized by central nervous system depression, metabolic acidosis, gasping respirations, and high levels of benzyl alcohol and its metabolites found in the blood and urine) has been associated with benzyl alcohol dosages >99 mg/kg/day in neonates and low-birth weight neonates. Additional symptoms may include gradual neurological deterioration, seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, hematologic abnormalities, skin breakdown, hepatic and renal failure, hypotension, bradycardia, andcardiovascular collapse.

Although normal therapeutic doses of this product deliver amounts of benzyl alcohol that are substantially lower than those reported in association with the "gasping syndrome," the minimum amount of benzyl alcohol at which toxicity may occur is not known. Premature and low-birth weight infants, as well as patients receiving high dosages, may be more likely to develop toxicity. Practitioners administering this and other medications containing benzyl alcohol should consider the combined daily metabolic load of benzyl alcohol from all sources.

Published juvenile animal studies demonstrate that the administration of anesthetic and sedation drugs, such as propofol, that either block NMDA receptors or potentiate the activity of GABA during the period of rapid brain growth or synaptogenesis, results in wide spread neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell loss in the developing brain and alterations in synaptic morphology and neurogenesis. Based on comparisons across species, the window of vulnerability to these changes is believed to correlate with exposures in the third trimester of gestation through the first several months of life, but may extend out to approximately 3 years of age in humans.

In primates, exposure to 3 hours of ketamine that produced a light surgical plane of anesthesia did not increase neuronal cell loss, however, treatment regimens of 5 hours or longer of isoflurane increased neuronal cell loss. Data from isoflurane-treated rodents and ketamine-treated primates suggest that the neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell losses are associated with prolonged cognitive deficits in learning and memory. The clinical significance of these nonclinical findings is not known, and healthcare providers should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in pregnant women, neonates, and young children who require procedures with the potential risks suggested by the nonclinical data

Propofol injectable emulsion, USP is available in single-dose vials as follows:

200 mg of propofol per 20 mL of an oil-in-water emulsion (10 mg per mL), 20 mL vial

500 mg of propofol per 50 mL of an oil-in-water emulsion (10 mg per mL), 50 mL vial

1,000 mg of propofol per 100 mL of an oil-in-water emulsion (10 mg per mL), 100 mL vial

Propofol injectable emulsion is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to propofol or any of propofol injectable emulsion components.

Propofol injectable emulsion is contraindicated in patients with a history of anaphylaxis to eggs, egg products, soybeans or soy products.

The following serious or otherwise important adverse reactions are discussed elsewhere in the labeling:

• Hypersensitivity reaction

Use of propofol injectable emulsion has been associated with both fatal and life threatening anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions.

Clinical features of anaphylaxis, including angioedema, bronchospasm, erythema, and hypotension, occur rarely following propofol injectable emulsion administration.

• Hypotension and/or bradycardia

Propofol injectable emulsion has no vagolytic activity. Reports of bradycardia, asystole, and rarely, cardiac arrest have been associated with propofol injectable emulsion. Pediatric patients are susceptible to this effect, particularly when fentanyl is given concomitantly.

The intravenous administration of anticholinergic agents (e.g., atropine or glycopyrrolate) should be considered to modify potential increases in vagal tone due to concomitant agents (e.g., succinylcholine) or surgical stimuli.

• Propofol Infusion Syndrome

Use of propofol injectable emulsion infusions for both adult and pediatric ICU sedation has been associated with a constellation of metabolic derangements and organ system failures, referred to as Propofol Infusion Syndrome, that have resulted in death. The syndrome is characterized by severe metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, lipemia, rhabdomyolysis, hepatomegaly, renal failure, ECG changes (Coved ST segment elevation -similar to ECG changes of the Brugada syndrome) and/or cardiac failure.

The following appear to be major risk factors for the development of these events: decreased oxygen delivery to tissues; serious neurological injury and/or sepsis; high dosages of one or more of the following pharmacological agents: vasoconstrictors, steroids, inotropes and/or prolonged, high-dose infusions of propofol (> 5 mg/kg/hour for > 48 hours). The syndrome has also been reported following large-dose, short-term infusions during surgical anesthesia. In the setting of prolonged need for sedation, increasing propofol dose requirements to maintain a constant level of sedation, or onset of metabolic acidosis during administration of a propofol infusion, consideration should be given to using alternative means of sedation.

Prescribers should be alert to these events in patients with the above risk factors and immediately discontinue propofol when the above signs develop.

In the description below, rates of the more common events represent U.S/Canadian clinical study results. Less frequent events are also derived from publications and marketing experience in over 8 million patients; there are insufficient data to support an accurate estimate of their incidence rates. These studies were conducted using a variety of premedicants, varying lengths of surgical/diagnostic procedures, and various other anesthetic/sedative agents. Most adverse events were mild and transient.

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

The following estimates of adverse events for propofol include data from clinical trials in general anesthesia/MAC sedation (N=2889 adult patients). The adverse events listed below as probably causally related are those events in which the actual incidence rate in patients treated with propofol was greater than the comparator incidence rate in these trials. Therefore, incidence rates for anesthesia and MAC sedation in adults generally represent estimates of the percentage of clinical trial patients which appeared to have probable causal relationship.

The adverse experience profile from reports of 150 patients in the MAC sedation clinical trials is similar to the profile established with propofol during anesthesia (see Table 3 below). During MAC sedation clinical trials, significant respiratory events included cough, upper airway obstruction, apnea, hypoventilation, and dyspnea.

Generally, the adverse experience profile from reports of 506 propofol pediatric patients from 6 days through 16 years of age in the U.S/Canadian anesthesia clinical trials is similar to the profile established with propofol during anesthesia in adults. Although not reported as an adverse event in clinical trials, apnea is frequently observed in pediatric patients.

The following estimates of adverse events include data from clinical trials in ICU sedation (N=159 adult patients). Probably related incidence rates for ICU sedation were determined by individual case report form review. Probable causality was based upon an apparent dose response relationship and/or positive responses to rechallenge. In many instances the presence of concomitant disease and concomitant therapy made the causal relationship unknown.Therefore, incidence rates for ICU sedation generally represent estimates of the percentage of clinical trial patients which appeared to have a probable causal relationship.

Anesthesia/MAC Sedation | ICU Sedation | |

| Body as a Whole: | Anaphylaxis/Anaphylactoid reaction perinatal disorder, tachycardia, bigeminy, bradycardia, premature ventricular contractions, hemorrhage, ECG abnormal arrhythmia atrial, fever, extremities pain , anticholinergic syndrome, asthenia, awareness, chest pain, extremities pain, fever,increased drug effect, neck rigidity/stiffness, trunk pain | Fever, sepsis, trunkpain, whole body weakness |

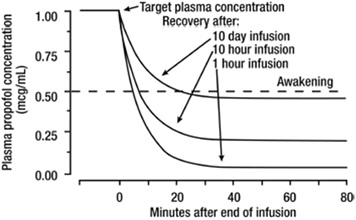

| Cardiovascular: | Premature atrial contractions Syncope, hypotension [see also Clinical Pharmacology ( Propofol injectable emulsion is an intravenous general anesthetic and sedation drug for use in the induction and maintenance of anesthesia or sedation. Intravenous injection of a therapeutic dose of propofol induces anesthesia, with minimal excitation, usually within 40 seconds from the start of injection (the time for one arm-brain circulation). As with other rapidly acting intravenous anesthetic agents, the half-time of the blood-brain equilibration is approximately 1 to 3 minutes, accounting for the rate of induction of anesthesia. The mechanism of action, like all general anesthetics, is poorly understood. However, propofol is thought to produce its sedative/anesthetic effects by the positive modulation of the inhibitory function of the neurotransmitter GABA through the ligand-gated GABAAreceptors. Pharmacodynamic properties of propofol are dependent upon the therapeutic blood propofol concentrations. Steady-state propofol blood concentrations are generally proportional to infusion rates. Undesirable side effects, such as cardiorespiratory depression, are likely to occur at higher blood concentrations which result from bolus dosing or rapid increases in infusion rates. An adequate interval (3 to 5 minutes) must be allowed between dose adjustments in order to assess clinical effects. The hemodynamic effects of propofol injectable emulsion during induction of anesthesia vary. If spontaneous ventilation is maintained, the major cardiovascular effect is arterial hypotension (sometimes greater than a 30% decrease) with little or no change in heart rate and no appreciable decrease in cardiac output. If ventilation is assisted or controlled (positive pressure ventilation), there is an increase in the incidence and the degree of depression of cardiac output. Addition of an opioid, used as a premedicant, further decreases cardiac output and respiratory drive. If anesthesia is continued by infusion of propofol injectable emulsion, the stimulation of endotracheal intubation and surgery may return arterial pressure towards normal. However, cardiac output may remain depressed. Comparative clinical studies have shown that the hemodynamic effects of propofol injectable emulsion during induction of anesthesia are generally more pronounced than with other intravenous induction agents. Induction of anesthesia with propofol injectable emulsion is frequently associated with apnea in both adults and pediatric patients. In adult patients who received propofol (2 mg/kg to 2.5 mg/kg), apnea lasted less than 30 seconds in 7% of patients, 30 seconds to 60 seconds in 24% of patients, and more than 60 seconds in 12% of patients. In pediatric patients from birth through 16 years of age assessable for apnea who received bolus doses of propofol (1 mg/kg to 3.6 mg/kg), apnea lasted less than 30 seconds in 12% of patients, 30 seconds to 60 seconds in 10% of patients, and more than 60 seconds in 5% of patients. During maintenance of general anesthesia, propofol injectable emulsion causes a decrease in spontaneous minute ventilation usually associated with an increase in carbon dioxide tension which may be marked depending upon the rate of administration and concurrent use of other medications (e.g., opioids, sedatives, etc.). During monitored anesthesia care (MAC) sedation, attention must be given to the cardiorespiratory effects of propofol injectable emulsion. Hypotension, oxyhemoglobin desaturation, apnea, and airway obstruction can occur, especially following a rapid bolus of propofol injectable emulsion. During initiation of MAC sedation, slow infusion or slow injection techniques are preferable over rapid bolus administration. During maintenance of MAC sedation, a variable rate infusion is preferable over intermittent bolus administration in order to minimize undesirable cardiorespiratory effects. In the elderly, debilitated, or ASA-PS III or IV patients, rapid (single or repeated) bolus dose administration should not be used for MAC sedation [see Warnings and Precautions ( 5.12) ].Clinical and preclinical studies suggest that propofol is rarely associated with elevation of plasma histamine levels. Preliminary findings in patients with normal intraocular pressure indicate that propofol injectable emulsion produces a decrease in intraocular pressure which may be associated with a concomitant decrease in systemic vascular resistance. Clinical studies indicate that propofol when used in combination with hypocarbia increases cerebrovascular resistance and decreases cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic oxygen consumption, and intracranial pressure. Propofol does not affect cerebrovascular reactivity to changes in arterial carbon dioxide tension [see Clinical Studies ( 14.2)]. Clinical studies indicate that propofol does not suppress the adrenal response to ACTH. Animal studies and limited experience in susceptible patients have not indicated any propensity of propofol to induce malignant hyperthermia. The pharmacokinetics of propofol are well described by a three-compartment linear model with compartments representing the plasma, rapidly equilibrating tissues, and slowly equilibrating tissues. Following an intravenous bolus dose, there is rapid equilibration between the plasma and the brain, accounting for the rapid onset of anesthesia. Plasma levels initially decline rapidly as a result of both distribution and metabolic clearance. Distribution accounts for about half of this decline following a bolus of propofol. However, distribution is not constant over time, but decreases as body tissues equilibrate with plasma and become saturated. The rate at which equilibration occurs is a function of the rate and duration of the infusion. When equilibration occurs there is no longer a net transfer of propofol between tissues and plasma. Discontinuation of the recommended doses of propofol after the maintenance of anesthesia for approximately one hour, or for sedation in the ICU for one day, results in a prompt decrease in blood propofol concentrations and rapid awakening. Longer infusions (10 days of ICU sedation) result in accumulation of significant tissue stores of propofol, such that the reduction in circulating propofol is slowed and the time to awakening is increased. By daily titration of propofol dosage to achieve only the minimum effective therapeutic concentration, rapid awakening within 10 to 15 minutes can occur even after long-term administration. If, however, higher than necessary infusion levels have been maintained for a long time, propofol redistribution from fat and muscle to the plasma can be significant and slow recovery. The figure below illustrates the fall of plasma propofol levels following infusions of various durations to provide ICU sedation.  The large contribution of distribution (about 50%) to the fall of propofol plasma levels following brief infusions means that after very long infusions a reduction in the infusion rate is appropriate by as much as half the initial infusion rate in order to maintain a constant plasma level. Therefore, failure to reduce the infusion rate in patients receiving propofol for extended periods may result in excessively high blood concentrations of the drug. Thus, titration to clinical response and daily evaluation of sedation levels are important during use of propofol infusion for ICU sedation. Adults Propofol clearance ranges from 23 mL/kg/min to 50 mL/kg/min (1.6 L/min to 3.4 L/min in 70 kg adults). It is chiefly eliminated by hepatic conjugation to inactive metabolites which are excreted by the kidney. A glucuronide conjugate accounts for about 50% of the administered dose. Propofol has a steady-state volume of distribution (10-day infusion) approaching 60 L/kg in healthy adults. A difference in pharmacokinetics due to gender has not been observed. The terminal half-life of propofol after a 10-day infusion is 1 day to 3 days. Geriatrics With increasing patient age, the dose of propofol needed to achieve a defined anesthetic end point (dose-requirement) decreases. This does not appear to be an age-related change in pharmacodynamics or brain sensitivity, as measured by EEG burst suppression. With increasing patient age, pharmacokinetic changes are such that, for a given intravenous bolus dose, higher peak plasma concentrations occur, which can explain the decreased dose requirement. These higher peak plasma concentrations in the elderly can predispose patients to cardiorespiratory effects including hypotension, apnea, airway obstruction, and/or arterial oxygen desaturation. The higher plasma levels reflect an age-related decrease in volume of distribution and intercompartmental clearance. Lower doses are therefore recommended for initiation and maintenance of sedation and anesthesia in elderly patients [see Dosage and Administration ( 2)] .Pediatrics The pharmacokinetics of propofol were studied in children between 3 years and 12 years of age who received propofol for periods of approximately 1 to 2 hours. The observed distribution and clearance of propofol in these children were similar to adults. Organ Failure The pharmacokinetics of propofol do not appear to be different in people with chronic hepatic cirrhosis or chronic renal impairment compared to adults with normal hepatic and renal function. The effects of acute hepatic or renal failure on the pharmacokinetics of propofol have not been studied [See Specific Populations ( 8.6) and ].)], tachycardia Nodal,arrhythmia Bradycardia, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular heart block, bigeminy, bleeding, bundle branch block, cardiac arrest, ECG abnormal, edema, extrasystole, heart block, hypertension, myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, premature ventricular contractions, ST segment depression, supraventricular tachycardia, tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation | Bradycardia, decreased cardiac output, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, bigeminy, cardiac arrest, extrasystole, rightheart failure, ventricular tachycardia |

| Central Nervous System: | Hypertonia/Dystonia, paresthesia, movement, abnormal dreams, agitation, amorous behavior, anxiety, bucking/jerking/thrashing, chills/shivering/clonic/myoclonic movement, combativeness, confusion, delirium, depression, dizziness, emotional lability, euphoria, fatigue, hallucinations, headache, hypotonia, hysteria, insomnia, moaning, neuropathy, opisthotonos, rigidity, seizures, somnolence, tremor, twitching | Agitation, hypotension, hills/shivering, intracranial hypertension, seizures, somnolence, thinking abnormal |

| Digestive: | Hypersalivation, nausea, cramping, diarrhea, dry mouth, enlarged parotid, nausea, swallowing, vomiting | Ileus, liver function abnormal |

| Hemic/Lymphatic: | Leukocytosis, coagulation disorder, leukocytosis | |

| Injection Site: | Phlebitis, pruritus, burning/Stinging or pain, hives/itching, phlebitis, redness/discoloration | |

| Metabolic/Nutritional: | hypomagnesemia, hyperkalemia, hyperlipemia | BUN increased, creatinine increased, dehydration, hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, osmolality increased, hyperlipemia |

| Musculoskeletal: | Myalgia | |

| Nervous: | Dizziness, agitation, chills, somnolenceDelirium | |

| Respiratory: | Wheezing, cough, laryngospasm, hypoxia, apnea, bronchospasm, burning in throat,dyspnea, hiccough, hyperventilation, hypoventilation, pharyngitis, sneezing, tachypnea, upper airway obstruction | Decreased lung function, respiratory acidosis during weaning, hypoxia |

| Skin and Appendages: | Flushing, Pruritus, rash,conjunctival hyperemia, diaphoresis, urticaria | Rash |

| Special Senses: | Amblyopia, vision abnormal, diplopia, ear pain, eye pain, nystagmus, taste perversion, tinnitus | |

| Urogenital: | Cloudy urine, oliguria, urine retention | Green urine, kidneyfailure |

During the post-marketing period, there have been rare reports of local pain, swelling, blisters, and/or tissue necrosis following accidental extravasation of propofol injectable emulsion

Phlebitis or venous thrombosis has been reported. In two clinical studies using dedicated intravenous catheters, no instances of venous sequelae were observed up to 14 days following induction.

Accidental intra-arterial injection has been reported in patients, and, other than pain, there were no major sequelae.

Venous sequelae, i.e., phlebitis or thrombosis, have been reported rarely (<1%).

The induction dose requirements of propofol injectable emulsion may be reduced in patients with intramuscular or intravenous premedication, particularly with opioids (e.g., morphine, meperidine, and fentanyl, etc.) and combinations of opioids and sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates, chloral hydrate, droperidol, etc.). These agents may increase the anesthetic or sedative effects of propofol injectable emulsion and may also result in more pronounced decreases in systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressures and cardiac output.

In pediatric patients, administration of fentanyl concomitantly with propofol injectable emulsion may result in serious bradycardia.

During maintenance of anesthesia or sedation, the rate of propofol injectable emulsion administration should be adjusted according to the desired level of anesthesia or sedation and may be reduced in the presence of supplemental analgesic agents (e.g., nitrous oxide or opioids).

The concurrent administration of potent inhalational agents (e.g., isoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, enflurane, and halothane) during maintenance with propofol injectable emulsion are routinely used. These inhalational agents can also be expected to increase the anesthetic or sedative and cardiorespiratory effects of propofol injectable emulsion.

The concomitant use of valproate and propofol may lead to increased blood levels of propofol. Reduce the dose of propofol when co-administering with valproate. Monitor patients closely for signs of increased sedation or cardiorespiratory depression.

Propofol injectable emulsion does not cause a clinically significant change in onset, intensity or duration of action of the commonly used neuromuscular blocking agents (e.g., succinylcholine and nondepolarizing muscle relaxants).

No significant adverse interactions with commonly used premedications or drugs used during anesthesia or sedation (including a range of muscle relaxants, inhalational agents, analgesic agents, and local anesthetic agents) have been observed in adults.

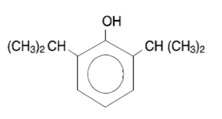

Propofol injectable emulsion, USP is an anesthetic available as a sterile, nonpyrogenic white or almost white homogeneous emulsion for intravenous administration. The structural formula is:

Chemical name: 2,6 diisopropylphenol

Molecular formula: C12H18O

Molecular weight:178.27

Propofol, USP is slightly soluble in water. The pKa is 11. The octanol/water partition coefficient for propofol is 6761:1 at a pH of 4.5 to 7.4.

Each mL of propofol injectable emulsion, USP contains 10 mg of propofol, 100 mg of soybean oil (100 mg/mL), 22.5 mg of glycerol (22.5 mg/mL), 12 mg of purified egg phospholipids (12 mg/mL), and benzyl alcohol (0.15%); with sodium hydroxide to adjust pH, in water for injection. Propofol injectable emulsion is isotonic and has a pH of 5.5 to 7.4.