Dosage & Administration

By using PrescriberAI, you agree to the AI Terms of Use.

Kisunla Prescribing Information

Monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

In Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.

One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

The radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

aIncludes new or worsening superficial siderosis. | |||

ARIA Type | Radiographic Severity | ||

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | FLAIR hyperintensity confined to sulcus and/or cortex/subcortex white matter in one location <5 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity 5 to 10 cm in single greatest dimension, or more than 1 site of involvement, each measuring <10 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity >10 cm with associated gyral swelling and sulcal effacement. One or more separate/independent sites of involvement may be noted. |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | Less than or equal to 4 new incident microhemorrhages | 5 to 9 new incident microhemorrhages | 10 or more new incident microhemorrhages |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 1 newafocal area of superficial siderosis | 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis | Greater than 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis |

*Administered as Dosing Regimen 2 over 12 months of treatment | ||||||

| Study 1 Dosing Regimen 1 N=853 % | Study 2 Dosing Regimen 2 N=212 % | |||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | 7 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 2 |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity

Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended

There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E.

Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs.

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

A lower incidence of ARIA occurred with the dosing regimen administered in Study 2 (350 mg/700 mg/1,050 mg/1,400 mg; Dosing Regimen 2) as compared to the regimen administered in Study 1 (700 mg/700 mg/700 mg/1,400 mg; Dosing Regimen 1); therefore, Dosing Regimen 2 is recommended for administration of KISUNLA

The safety of KISUNLA has been evaluated in 3727 patients with Alzheimer's disease who received at least one dose of KISUNLA intravenously. In the other clinical studies of KISUNLA, 1912 patients with Alzheimer's disease received KISUNLA once monthly for at least 6 months, 1057 patients for at least 12 months, and 432 patients for at least 18 months, at the Dosing Regimen 1.

In Study 1 (NCT04437511), a total of 853 patients with Alzheimer's disease received at least one dose of KISUNLA; patients were randomized to receive KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 1 or placebo.

Thirteen percent of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to 4% of patients on placebo stopped study treatment because of an adverse reaction. The most common adverse reaction leading to discontinuation of KISUNLA was infusion-related reaction (4% of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to no patient on placebo).

Table 7shows adverse reactions that were reported in at least 5% of patients treated with KISUNLA and at least 2% more frequently than in patients on placebo in Study 1.

aAdministered as a different titration regimen (700 mg/700 mg/700 mg/1,400 mg) than the currently recommended dosing regimen (350 mg/700 mg/1,050 mg/1,400 mg) | ||

bAs assessed by MRI. A participant could have both microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. | ||

Adverse Reaction | KISUNLA a N = 853 % | Placebo N = 874 % |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhageb | 25 | 11 |

| ARIA-E | 24 | 2 |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosisb | 15 | 3 |

| Headache | 13 | 10 |

| Infusion-related reaction | 9 | 0.5 |

In Study 2 (NCT05738486), a total of 842 patients received at least one dose of KISUNLA; 212 patients were randomized to receive KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2. In Study 2, compared to the rates reported with Dosing Regimen 1, higher rates of hypersensitivity reactions (8% of patients treated with Dosing Regimen 2) and infusion-related reactions (16% of patients treated with Dosing Regimen 2), and a lower rate of ARIA-E (16% of patients treated with Dosing Regimen 2) were observed

Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, occurred in 3% of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to 0.7% of patients on placebo in Study 1 and in 8% of patients treated with KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 in Study 2.

Serious adverse reactions of intestinal obstruction occurred in three patients (0.4%) treated with KISUNLA compared to no patients on placebo in Study 1 and one patient (0.5%) treated with KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 in Study 2. Serious adverse reactions of intestinal perforation occurred in two patients (0.2%) treated with KISUNLA compared to one patient (0.1%) on placebo in Study 1.

Infusion-related reactions occurred more frequently in patients treated with KISUNLA who developed anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) compared to patients who did not develop ADAs (Study 1, Dosing Regimen 1: 10% compared to 2%; Study 2, Dosing Regimen 2: 20% compared to 8%).

Monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

In Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.

One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

The radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

aIncludes new or worsening superficial siderosis. | |||

ARIA Type | Radiographic Severity | ||

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | FLAIR hyperintensity confined to sulcus and/or cortex/subcortex white matter in one location <5 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity 5 to 10 cm in single greatest dimension, or more than 1 site of involvement, each measuring <10 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity >10 cm with associated gyral swelling and sulcal effacement. One or more separate/independent sites of involvement may be noted. |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | Less than or equal to 4 new incident microhemorrhages | 5 to 9 new incident microhemorrhages | 10 or more new incident microhemorrhages |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 1 newafocal area of superficial siderosis | 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis | Greater than 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis |

*Administered as Dosing Regimen 2 over 12 months of treatment | ||||||

| Study 1 Dosing Regimen 1 N=853 % | Study 2 Dosing Regimen 2 N=212 % | |||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | 7 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 2 |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity

Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended

There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E.

Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs.

Monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

In Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.

One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

The radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

aIncludes new or worsening superficial siderosis. | |||

ARIA Type | Radiographic Severity | ||

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | FLAIR hyperintensity confined to sulcus and/or cortex/subcortex white matter in one location <5 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity 5 to 10 cm in single greatest dimension, or more than 1 site of involvement, each measuring <10 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity >10 cm with associated gyral swelling and sulcal effacement. One or more separate/independent sites of involvement may be noted. |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | Less than or equal to 4 new incident microhemorrhages | 5 to 9 new incident microhemorrhages | 10 or more new incident microhemorrhages |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 1 newafocal area of superficial siderosis | 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis | Greater than 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis |

*Administered as Dosing Regimen 2 over 12 months of treatment | ||||||

| Study 1 Dosing Regimen 1 N=853 % | Study 2 Dosing Regimen 2 N=212 % | |||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | 7 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 2 |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity

Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended

There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E.

Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs.

Monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

In Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.

One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

The radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

aIncludes new or worsening superficial siderosis. | |||

ARIA Type | Radiographic Severity | ||

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | FLAIR hyperintensity confined to sulcus and/or cortex/subcortex white matter in one location <5 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity 5 to 10 cm in single greatest dimension, or more than 1 site of involvement, each measuring <10 cm. | FLAIR hyperintensity >10 cm with associated gyral swelling and sulcal effacement. One or more separate/independent sites of involvement may be noted. |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | Less than or equal to 4 new incident microhemorrhages | 5 to 9 new incident microhemorrhages | 10 or more new incident microhemorrhages |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 1 newafocal area of superficial siderosis | 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis | Greater than 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis |

*Administered as Dosing Regimen 2 over 12 months of treatment | ||||||

| Study 1 Dosing Regimen 1 N=853 % | Study 2 Dosing Regimen 2 N=212 % | |||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| ARIA-E | 7 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

| ARIA-H microhemorrhage | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 2 |

| ARIA-H superficial siderosis | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity

Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended

There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E.

Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs.

The effectiveness of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease was established by Study 1, which assessed Dosing Regimen 1 (700 mg every 4 weeks for the first 3 doses, and then 1,400 mg every 4 weeks). Study 2 was conducted to assess different titration regimens, including Dosing Regimen 2 (doses every 4 weeks with 350 mg the first infusion, 700 mg the second infusion, 1,050 mg the third infusion, and then 1,400 mg every 4 weeks) that demonstrated comparable pharmacodynamic effects on amyloid plaque reduction with a reduced incidence of ARIA-related events compared to Dosing Regimen 1

The efficacy of KISUNLA was evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study (Study 1, NCT04437511) in patients with Alzheimer's disease (patients with confirmed presence of amyloid pathology and mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, consistent with Stage 3 and Stage 4 Alzheimer's disease). Patients were enrolled with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≥20 and ≤28 and had a progressive change in memory function for at least 6 months. Patients were included in the study based on visual assessment of tau PET imaging with flortaucipir and standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR). Patients were enrolled with or without concomitant approved therapies (cholinesterase inhibitors and the N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist memantine) for Alzheimer's disease. Patients could enroll in an optional, long-term extension.

In Study 1, 1736 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 700 mg of KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 1 (N = 860) or placebo (N = 876) for a total of up to 72 weeks. The treatment was switched to placebo based on amyloid PET levels measured at Week 24, Week 52, and Week 76. If the amyloid plaque level was <11 Centiloids on a single PET scan or 11 to <25 Centiloids on 2 consecutive PET scans, the patient was eligible to be switched to placebo.

Additionally, dose adjustments were allowed for treatment-emergent ARIA or symptoms that then showed ARIA-E or ARIA-H on MRI.

At baseline, mean age was 73 years, with a range of 59 to 86 years. Of the total number of patients randomized, 68% had low/medium tau level and 32% had high tau level; 71% were ApoE ε4 carriers and 29% were ApoE ε4 noncarriers. Fifty-seven percent of patients were female, 91% were White, 6% were Asian, 4% were Hispanic or Latino, and 2% were Black or African American.

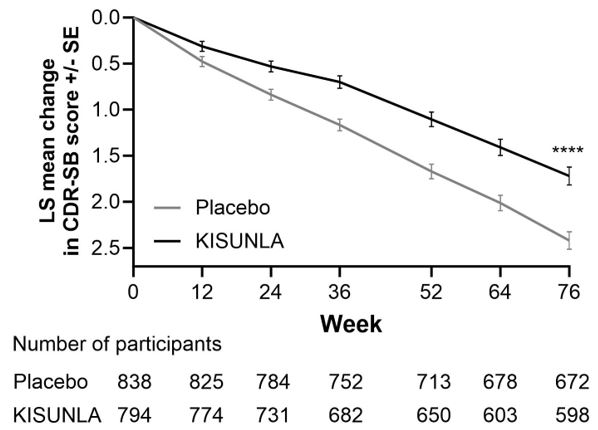

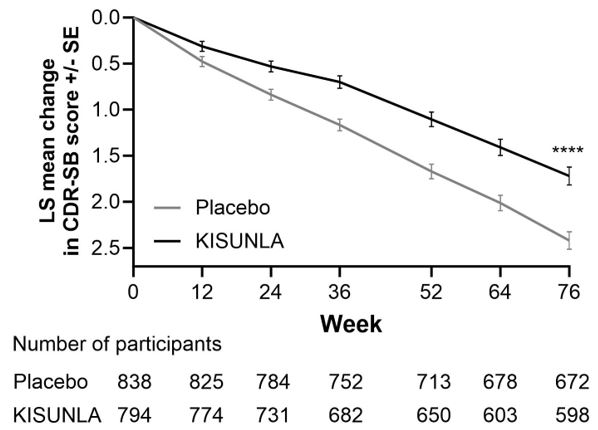

The primary efficacy endpoint was change in the integrated Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (iADRS) score from baseline to 76 weeks. The iADRS is a combination of two scores: the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog13) and the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study – instrumental Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-iADL) scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 144, with lower scores reflecting worse cognitive and functional performance. Other efficacy endpoints included Clinical Dementia Rating Scale – Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), ADAS-Cog13, and ADCS-iADL.

There were two primary analysis populations based on tau PET imaging with flortaucipir: 1) low/medium tau level population (defined by visual assessment and SUVR of ≥1.10 and ≤1.46), and 2) combined population of low/medium plus high tau (defined by visual assessment and SUVR >1.46) population.

Patients treated with KISUNLA demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in clinical decline on iADRS compared to placebo at Week 76 in the combined population (2.92, p<0.0001) and the low/medium tau population (3.25, p<0.0001).

Patients treated with KISUNLA demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in clinical decline on CDR-SB compared to placebo at Week 76 in the combined population (-0.70, p<0.0001) (

Dosing was continued or stopped in response to observed effects on amyloid imaging. The percentages of patients eligible for switch to placebo based on amyloid PET levels at Week 24, Week 52, and Week 76 timepoints were 17%, 47%, and 69%, respectively. Amyloid PET values may increase after treatment with donanemab is stopped

a****p<0.0001 versus placebo.

aAbbreviations: ADAS-Cog13= Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale – 13-item Cognitive Subscale; ADCS-iADL = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study – instrumental Activities of Daily Living subscale; CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating Scale – Sum of Boxes; NCS2 = natural cubic spline with 2 degrees of freedom; MMRM = mixed model for repeated measures. | ||

bAssessed using MMRM analysis. | ||

cAssessed using NCS2 analysis. | ||

dPercent slowing of decline relative to placebo: difference of adjusted mean change from baseline between treatment groups divided by adjusted mean change from baseline of placebo group at Week 76. | ||

Clinical Endpoints | KISUNLA (N = 860) | Placebo (N = 876) |

CDR-SB b | ||

| Mean baseline | 3.92 | 3.89 |

| Adjusted mean change from baseline | 1.72 | 2.42 |

| Difference from placebo (%)d | -0.70 (29%) p<0.0001 | -- |

ADAS-Cog 13 c | ||

| Mean baseline | 28.53 | 29.16 |

| Adjusted mean change from baseline | 5.46 | 6.79 |

| Difference from placebo (%)d | -1.33 (20%) p=0.0006 | -- |

ADCS-iADL c | ||

| Mean baseline | 47.96 | 47.98 |

| Adjusted mean change from baseline | -4.42 | -6.13 |

| Difference from placebo (%)d | 1.70 (28%) p=0.0001 | -- |

Study 2 (NCT05738486) was a randomized, double-blind study investigating the effect of different KISUNLA dosing regimens on ARIA-E and change from baseline in amyloid in adults with Alzheimer's disease (patients with confirmed amyloid pathology and mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as Study 1 except that tau PET was not an inclusion criterion. Patients were randomized to receive Dosing Regimen 1 (N=207), or one of three alternative regimens, including Dosing Regimen 2 (N=212) in a 1:1:1:1 ratio

Of the 212 patients receiving Dosing Regimen 2, the mean age was 74 years. Fifty-nine percent were female, 91% were White, 6.6% were Black or African American, 5.2% were Hispanic or Latino, and 1.4% were Asian. Overall, 65% of these patients were ApoE ε4 carriers, with 55% heterozygotes and 10% homozygotes, and 36% were noncarriers.

The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with any occurrence of ARIA-E. The results showed that patients receiving Dosing Regimen 2 had less incidence of ARIA-E by Week 52 compared with patients receiving Dosing Regimen 1 (

ARIA-E occurred at a higher incidence in ApoE ε4 homozygotes, compared to heterozygotes, with the lowest incidence in noncarriers. The small number of events and limited exposure in the ApoE ε4 subgroups limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA-E.

1Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative incidence | ||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, RD = risk difference | ||

Dosing Regimen 1 | Dosing Regimen 2 | |

N=207 | N=212 | |

ARIA-E Overall | ||

| n (incidence, %) | 50 (24.9) | 33 (16.2) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 8.7 (0.8, 16.5) |

ARIA-H Overall | ||

| n (incidence, %) | 56 (28.1) | 51 (25.2) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 2.9 (-5.8, 11.6) |

Homozygotes, N | 21 | 21 |

| ARIA-E | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 12 (57.1) | 5 (24.4) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 32.7 (4.4, 60.9) |

| ARIA-H | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 10 (47.6) | 6 (28.6) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 19.0 (-9.8, 47.8) |

Heterozygotes, N | 112 | 115 |

| ARIA-E | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 27 (25.0) | 18 (16.4) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 8.6 (-2.2, 19.3) |

| ARIA-H | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 34 (31.8) | 33 (30.8) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 1.0 (-11.5, 13.5) |

ApoE noncarriers, N | 72 | 75 |

| ARIA-E | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 11 (15.6) | 10 (13.8) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 1.8 (-9.8, 13.5) |

| ARIA-H | ||

| n (incidence1, %) | 12 (17.2) | 12 (16.4) |

| RD (95% CI) | - | 0.8 (-11.5, 13.1) |

| Boxed Warning | 07/2025 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dosage and Administration (Administer KISUNLA every four weeks as an intravenous infusion over approximately 30 minutes with the recommended dosage and dosing schedule described in Table 1. KISUNLA must be diluted prior to administration ( see Table 4).

Consider stopping dosing with KISUNLA based on reduction of amyloid plaques to minimal levels on amyloid PET imaging. In Study 1 and Study 2, dosing was stopped based on a reduction of amyloid levels below predefined thresholds on PET imaging [see Clinical Studies ] .If an infusion is missed, resume administration every 4 weeks at the same dose as soon as possible. KISUNLA can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities -edema (ARIA-E) and -hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H) [see Warnings and Precautions and Adverse Reactions ] .Monitoring for ARIA Obtain a recent baseline brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to initiating treatment with KISUNLA. Obtain an MRI prior to the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 7thinfusions. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including an MRI if indicated. Recommendations for Dosing Interruptions in Patients with ARIA ARIA-E The recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-E are provided in Table 2.

ARIA-H The recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-H are provided in Table 3.

| 07/2025 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Warnings and Precautions (Monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together. ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA. Study 1 and Study 2 Overview [see Clinical Studies ] In Study 1, safety was assessed in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 1 (n = 853) compared to those who received placebo (n = 874). In Study 2, the effect of different dosing regimens of KISUNLA on ARIA was assessed, including in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=212), which is the recommended dosage and described below.Incidence of ARIA A lower incidence of ARIA was observed with Dosing Regimen 2 as compared to Dosing Regimen 1. Therefore, Dosing Regimen 2 is the recommended dosage for KISUNLA.In Study 1, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 6% of patients through 18 months of treatment with KISUNLA[see Adverse Reactions ] . Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 85% of those patients. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 36%, 24%, and 31% of patients treated with KISUNLA, respectively, compared to 14%, 2%, and 13% of patients on placebo, respectively. There was no increase in isolated ARIA-H (i.e., ARIA-H in patients who did not also experience ARIA-E) for KISUNLA compared to placebo.In Study 2, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 3% of patients and symptomatic ARIA-H occurred in less than 1% of patients through 12 months of treatment with KISUNLA[ see Adverse Reactions ] . Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 67% of patients at 12 months. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 29%, 16%, and 25% of patients treated with KISUNLA.Incidence of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was reported in 0.5% of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to 0.2% of patients on placebo in Study 1, and in 1% of patients treated with KISUNLA in Study 2. Fatal events of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking KISUNLA have been observed.Risk Factors for ARIA and Intracerebral Hemorrhage ApoE ε4 Carrier Status The risk of ARIA, including symptomatic and serious ARIA, is increased in apolipoprotein E ε4 (ApoE ε4) homozygotes, which include approximately 15% of Alzheimer's disease patients.In Study 1, of patients in the KISUNLA arm (n=850), 17% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 53% were heterozygotes, and 30% were noncarriers. The incidence of ARIA through 18 months was higher in ApoE ε4 homozygotes (55% on KISUNLA vs. 22% on placebo) than in heterozygotes (36% on KISUNLA vs. 13% on placebo) and noncarriers (25% on KISUNLA vs. 12% on placebo). Among patients treated with KISUNLA, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 8% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 7% of heterozygotes and 4% of noncarriers. Serious events of ARIA occurred in 3% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 2% of heterozygotes, and 1% of noncarriers.In Study 2, of patients treated with KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=211), 10% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 55% were heterozygotes, and 36% were noncarriers. Symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 0% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 4% of heterozygotes and 3% of noncarriers. The small number of events and limited exposure in the ApoE ε4 subgroups limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA-E.The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status [see Dosage and Administration ] . Testing for ApoE ε4 status should be performed prior to initiation of treatment to inform the risk of developing ARIA. Prior to testing, prescribers should discuss with patients the risk of ARIA across genotypes and the implications of genetic testing results. Prescribers should inform patients that if genotype testing is not performed, they can still be treated with KISUNLA; however, it cannot be determined if they are ApoE ε4 homozygotes and at a higher risk for ARIA. An FDA-authorized test for detection of ApoE ε4 alleles to identify patients at risk of ARIA if treated with KISUNLA is not currently available. Currently available tests used to identify ApoE ε4 alleles may vary in accuracy and design.Radiographic Findings of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema. Concomitant Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic Medication In Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications. One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Radiographic Severity The radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

Monitoring and Dose Management Guidelines Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity [see Dosage and Administration ] . Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-H depend on the type of ARIA-H and radiographic severity[see Dosage and Administration ] . Use clinical judgment in considering whether to continue dosing in patients with recurrent ARIA-E.Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended [see Dosage and Administration ] . Enhanced clinical vigilance for ARIA is recommended during the first 24 weeks of treatment with KISUNLA. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including MRI if indicated. If ARIA is observed on MRI, careful clinical evaluation should be performed prior to continuing treatment.There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E. Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs. In Study 1, infusion-related reactions were observed in 9% of patients treated with KISUNLA, the majority (70%) of which occurred within the first 4 infusions, compared to 0.5% of patients on placebo. Infusion-related reactions were mostly mild (57%) or moderate (39%) in severity. Infusion-related reactions resulted in discontinuations in 4% of patients treated with KISUNLA.In Study 2, infusion-related reactions associated with KISUNLA occurred in 16% of patients; the majority (88%) occurred within the first 4 infusions. Infusion-related reactions were mostly mild (47%) or moderate (50%) in severity. Infusion-related reactions resulted in discontinuations in 2.8% of patients treated with KISUNLA.Most infusion-related reactions associated with KISUNLA occurred during the infusion or within 30 minutes after completion of the infusion, however some have occurred hours after an infusion. Signs and symptoms of infusion-related reactions include chills, erythema, nausea/vomiting, flushing, difficulty breathing/dyspnea, sweating, elevated blood pressure, headache, chest pain, and low blood pressure. In the event of an infusion-related reaction, the infusion rate may be reduced, or the infusion may be discontinued, and appropriate therapy initiated as clinically indicated. Consider pre-treatment with antihistamines, acetaminophen, or corticosteroids prior to subsequent dosing. | 07/2025 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

KISUNLATM is indicated for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Treatment with KISUNLA should be initiated in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which treatment was initiated in the clinical trials.

- Confirm the presence of amyloid beta pathology prior to initiating treatment. ()

2.1 Patient SelectionConfirm the presence of amyloid beta pathology prior to initiating treatment

[see Clinical Pharmacology ]. -

Administer KISUNLA as an intravenous infusion over approximately 30 minutes every four weeks as follows ():

2.2 Dosing InstructionsAdminister KISUNLA every four weeks as an intravenous infusion over approximately 30 minutes with the recommended dosage and dosing schedule described in Table 1. KISUNLA must be diluted prior to administration (seeTable 4).Table 1: Recommended Dosage* and Dosing Schedule *Dosing Regimen 2

[see Warnings and Precautions and Clinical Studies ]Intravenous Infusion(every 4 weeks)KISUNLA Dosage(administered over approximately 30 minutes)Infusion 1 350 mg Infusion 2 700 mg Infusion 3 1,050 mg Infusion 4 and beyond 1,400 mg Consider stopping dosing with KISUNLA based on reduction of amyloid plaques to minimal levels on amyloid PET imaging. In Study 1 and Study 2, dosing was stopped based on a reduction of amyloid levels below predefined thresholds on PET imaging

[see Clinical Studies ].If an infusion is missed, resume administration every 4 weeks at the same dose as soon as possible.

- Infusion 1: 350 mg

- Infusion 2: 700 mg

- Infusion 3: 1,050 mg

- Infusion 4 and beyond: 1,400 mg

- Consider stopping dosing with KISUNLA based on reduction of amyloid plaques to minimal levels on amyloid PET imaging. ()

2.2 Dosing InstructionsAdminister KISUNLA every four weeks as an intravenous infusion over approximately 30 minutes with the recommended dosage and dosing schedule described in Table 1. KISUNLA must be diluted prior to administration (seeTable 4).Table 1: Recommended Dosage* and Dosing Schedule *Dosing Regimen 2

[see Warnings and Precautions and Clinical Studies ]Intravenous Infusion(every 4 weeks)KISUNLA Dosage(administered over approximately 30 minutes)Infusion 1 350 mg Infusion 2 700 mg Infusion 3 1,050 mg Infusion 4 and beyond 1,400 mg Consider stopping dosing with KISUNLA based on reduction of amyloid plaques to minimal levels on amyloid PET imaging. In Study 1 and Study 2, dosing was stopped based on a reduction of amyloid levels below predefined thresholds on PET imaging

[see Clinical Studies ].If an infusion is missed, resume administration every 4 weeks at the same dose as soon as possible.

- Obtain a recent baseline brain MRI prior to initiating treatment. (,

2.3 Monitoring and Dosing Interruption for Amyloid Related Imaging AbnormalitiesKISUNLA can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities -edema (ARIA-E) and -hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H)

[see Warnings and Precautions and Adverse Reactions ].Monitoring for ARIAObtain a recent baseline brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to initiating treatment with KISUNLA. Obtain an MRI prior to the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 7thinfusions. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including an MRI if indicated.

Recommendations for Dosing Interruptions in Patients with ARIAARIA-EThe recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-E are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Dosing Recommendations for Patients With ARIA-Ec aMild: discomfort noticed, but no disruption of normal daily activity.

Moderate: discomfort sufficient to reduce or affect normal daily activity.

Severe: incapacitating, with inability to work or to perform normal daily activity.bSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic resolution and symptoms, if present, resolve; consider a follow-up MRI to assess for resolution 2 to 4 months after initial identification. Resumption of dosing should be guided by clinical judgment.

cSee Table 5for MRI radiographic severity

[Warning and Precautions ].Clinical Symptom SeverityaARIA-E Severity on MRIMildModerateSevereAsymptomaticMay continue dosing at current dose and schedule Suspend dosingb Suspend dosingb MildMay continue dosing based on clinical judgment Suspend dosingb Moderate or SevereSuspend dosingb ARIA-HThe recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-H are provided in Table 3.

In patients who develop intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter during treatment with KISUNLA, suspend dosing until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve. Use clinical judgment when considering whether to continue treatment or permanently discontinue KISUNLA after radiographic stabilization and resolution of symptoms.Table 3: Dosing Recommendations for Patients With ARIA-Hc aSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve; resumption of dosing should be guided by clinical judgment; consider a follow-up MRI to assess for stabilization 2 to 4 months after initial identification.

bSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve. Use clinical judgment when considering whether to continue treatment or permanently discontinue KISUNLA.

cSee Table 5for MRI radiographic severity

[Warning and Precautions ].Clinical Symptom SeverityARIA-H Severity on MRIMildModerateSevereAsymptomaticMay continue dosing at current dose and schedule Suspend dosinga Suspend dosingb SymptomaticSuspend dosinga Suspend dosinga )5.1 Amyloid Related Imaging AbnormalitiesMonoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

Study 1 and Study 2 Overview[see Clinical Studies ]In Study 1, safety was assessed in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 1 (n = 853) compared to those who received placebo (n = 874). In Study 2, the effect of different dosing regimens of KISUNLA on ARIA was assessed, including in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=212), which is the recommended dosage and described below.Incidence of ARIAA lower incidence of ARIA was observed with Dosing Regimen 2 as compared to Dosing Regimen 1. Therefore, Dosing Regimen 2 is the recommended dosage for KISUNLA.In Study 1, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 6% of patients through 18 months of treatment with KISUNLA[see Adverse Reactions ]. Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 85% of those patients. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 36%, 24%, and 31% of patients treated with KISUNLA, respectively, compared to 14%, 2%, and 13% of patients on placebo, respectively. There was no increase in isolated ARIA-H (i.e., ARIA-H in patients who did not also experience ARIA-E) for KISUNLA compared to placebo.In Study 2, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 3% of patients and symptomatic ARIA-H occurred in less than 1% of patients through 12 months of treatment with KISUNLA[see Adverse Reactions ]. Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 67% of patients at 12 months. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 29%, 16%, and 25% of patients treated with KISUNLA.Incidence of Intracerebral HemorrhageIntracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was reported in 0.5% of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to 0.2% of patients on placebo in Study 1, and in 1% of patients treated with KISUNLA in Study 2. Fatal events of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking KISUNLA have been observed.Risk Factors for ARIA and Intracerebral HemorrhageApoE ε4 Carrier StatusThe risk of ARIA, including symptomatic and serious ARIA, is increased in apolipoprotein E ε4 (ApoE ε4) homozygotes, which include approximately 15% of Alzheimer's disease patients.In Study 1, of patients in the KISUNLA arm (n=850), 17% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 53% were heterozygotes, and 30% were noncarriers. The incidence of ARIA through 18 months was higher in ApoE ε4 homozygotes (55% on KISUNLA vs. 22% on placebo) than in heterozygotes (36% on KISUNLA vs. 13% on placebo) and noncarriers (25% on KISUNLA vs. 12% on placebo). Among patients treated with KISUNLA, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 8% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 7% of heterozygotes and 4% of noncarriers. Serious events of ARIA occurred in 3% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 2% of heterozygotes, and 1% of noncarriers.In Study 2, of patients treated with KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=211), 10% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 55% were heterozygotes, and 36% were noncarriers. Symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 0% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 4% of heterozygotes and 3% of noncarriers. The small number of events and limited exposure in the ApoE ε4 subgroups limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA-E.The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

[see Dosage and Administration ]. Testing for ApoE ε4 status should be performed prior to initiation of treatment to inform the risk of developing ARIA. Prior to testing, prescribers should discuss with patients the risk of ARIA across genotypes and the implications of genetic testing results. Prescribers should inform patients that if genotype testing is not performed, they can still be treated with KISUNLA; however, it cannot be determined if they are ApoE ε4 homozygotes and at a higher risk for ARIA. An FDA-authorized test for detection of ApoE ε4 alleles to identify patients at risk of ARIA if treated with KISUNLA is not currently available. Currently available tests used to identify ApoE ε4 alleles may vary in accuracy and design.Radiographic Findings of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

Concomitant Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic MedicationIn Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.

One fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in a patient taking KISUNLA in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 1, and one fatal intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in the setting of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent in Study 2. Additional caution should be exercised when considering the administration of antithrombotics or a thrombolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator) to a patient already being treated with KISUNLA. Because ARIA-E can cause focal neurologic deficits that can mimic an ischemic stroke, treating clinicians should consider whether such symptoms could be due to ARIA-E before giving thrombolytic therapy in a patient being treated with KISUNLA.Caution should be exercised when considering the use of KISUNLA in patients with factors that indicate an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage and in particular for patients who need to be on anticoagulant therapy or patients with findings on MRI that are suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Radiographic SeverityThe radiographic severity of ARIA associated with KISUNLA was classified by the criteria shown in Table 5.

In Study 1, the majority of ARIA-E radiographic events occurred early in treatment (within the first 24 weeks), although ARIA can occur at any time and patients can have more than one episode. Resolution on MRI after the first ARIA-E event occurred in 63% of patients treated with KISUNLA by 12 weeks, 80% by 20 weeks, and 83% overall after detection. Among patients treated with KISUNLA, the rate of severe radiographic ARIA-E was highest in ApoE ε4 homozygotes (n=143) compared to heterozygotes (n=452) or noncarriers (n=255) at rates of 3%, 2%, and 0.4%, respectively. Among patients treated with KISUNLA, the rate of severe radiographic ARIA-H was highest in ApoE ε4 homozygotes (n=143) compared to heterozygotes (n=452) or noncarriers (n=255) at rates of 22%, 8%, and 4%, respectively. Table 6shows the maximum radiographic severity for ARIA-E, ARIA-H microhemorrhage, and ARIA-H superficial siderosis in Study 1 and Study 2.Table 5: ARIA MRI Classification Criteria aIncludes new or worsening superficial siderosis.

ARIA TypeRadiographic SeverityMildModerateSevereARIA-E FLAIR hyperintensity confined to sulcus and/or cortex/subcortex white matter in one location <5 cm. FLAIR hyperintensity 5 to 10 cm in single greatest dimension, or more than 1 site of involvement, each measuring <10 cm. FLAIR hyperintensity >10 cm with associated gyral swelling and sulcal effacement. One or more separate/independent sites of involvement may be noted. ARIA-H microhemorrhage Less than or equal to 4 new incident microhemorrhages 5 to 9 new incident microhemorrhages 10 or more new incident microhemorrhages ARIA-H superficial siderosis 1 newafocal area of superficial siderosis 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis Greater than 2 new focal areas of superficial siderosis Table 6: Maximum Radiographic Severity in Patients Treated with KISUNLA in Study 1 Study 2 *Administered as Dosing Regimen 2 over 12 months of treatment

Study 1

Dosing Regimen 1

N=853

%Study 2

Dosing Regimen 2

N=212

%Mild Moderate Severe Mild Moderate Severe ARIA-E 7 15 2 6 9 0 ARIA-H microhemorrhage 17 4 5 17 3 2 ARIA-H superficial siderosis 6 4 5 4 3 1 Monitoring and Dose Management GuidelinesRecommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-E depend on clinical symptoms and radiographic severity

[see Dosage and Administration ]. Recommendations for dosing in patients with ARIA-H depend on the type of ARIA-H and radiographic severity[see Dosage and Administration ]. Use clinical judgment in considering whether to continue dosing in patients with recurrent ARIA-E.Baseline brain MRI and periodic monitoring with MRI are recommended

[see Dosage and Administration ]. Enhanced clinical vigilance for ARIA is recommended during the first 24 weeks of treatment with KISUNLA. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including MRI if indicated. If ARIA is observed on MRI, careful clinical evaluation should be performed prior to continuing treatment.There is limited experience in patients who continued dosing through asymptomatic but radiographically mild to moderate ARIA-E. There are limited data for dosing patients who have experienced recurrent episodes of ARIA-E.

Providers should encourage patients to participate in real world data collection (e.g., registries) to help further the understanding of Alzheimer's disease and the impact of Alzheimer's disease treatments. Providers and patients can contact 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) for a list of currently enrolling programs.

- Obtain an MRI prior to the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 7th infusions. If radiographically observed ARIA occurs, treatment recommendations are based on type, severity, and presence of symptoms. (,

2.3 Monitoring and Dosing Interruption for Amyloid Related Imaging AbnormalitiesKISUNLA can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities -edema (ARIA-E) and -hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H)

[see Warnings and Precautions and Adverse Reactions ].Monitoring for ARIAObtain a recent baseline brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to initiating treatment with KISUNLA. Obtain an MRI prior to the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 7thinfusions. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including an MRI if indicated.

Recommendations for Dosing Interruptions in Patients with ARIAARIA-EThe recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-E are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Dosing Recommendations for Patients With ARIA-Ec aMild: discomfort noticed, but no disruption of normal daily activity.

Moderate: discomfort sufficient to reduce or affect normal daily activity.

Severe: incapacitating, with inability to work or to perform normal daily activity.bSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic resolution and symptoms, if present, resolve; consider a follow-up MRI to assess for resolution 2 to 4 months after initial identification. Resumption of dosing should be guided by clinical judgment.

cSee Table 5for MRI radiographic severity

[Warning and Precautions ].Clinical Symptom SeverityaARIA-E Severity on MRIMildModerateSevereAsymptomaticMay continue dosing at current dose and schedule Suspend dosingb Suspend dosingb MildMay continue dosing based on clinical judgment Suspend dosingb Moderate or SevereSuspend dosingb ARIA-HThe recommendations for dosing interruptions for patients with ARIA-H are provided in Table 3.

In patients who develop intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter during treatment with KISUNLA, suspend dosing until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve. Use clinical judgment when considering whether to continue treatment or permanently discontinue KISUNLA after radiographic stabilization and resolution of symptoms.Table 3: Dosing Recommendations for Patients With ARIA-Hc aSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve; resumption of dosing should be guided by clinical judgment; consider a follow-up MRI to assess for stabilization 2 to 4 months after initial identification.

bSuspend until MRI demonstrates radiographic stabilization and symptoms, if present, resolve. Use clinical judgment when considering whether to continue treatment or permanently discontinue KISUNLA.

cSee Table 5for MRI radiographic severity

[Warning and Precautions ].Clinical Symptom SeverityARIA-H Severity on MRIMildModerateSevereAsymptomaticMay continue dosing at current dose and schedule Suspend dosinga Suspend dosingb SymptomaticSuspend dosinga Suspend dosinga )5.1 Amyloid Related Imaging AbnormalitiesMonoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid, including KISUNLA, can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), characterized as ARIA with edema (ARIA-E), which can be observed on MRI as brain edema or sulcal effusions, and ARIA with hemosiderin deposition (ARIA-H), which includes microhemorrhage and superficial siderosis. ARIA can occur spontaneously in patients with Alzheimer's disease, particularly in patients with MRI findings suggestive of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, such as pretreatment microhemorrhage or superficial siderosis. ARIA-H associated with monoclonal antibodies directed against aggregated forms of beta amyloid generally occurs in association with an occurrence of ARIA-E. ARIA-H of any cause and ARIA-E can occur together.

ARIA usually occurs early in treatment and is usually asymptomatic, although serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur. ARIA can be fatal. When present, reported symptoms associated with ARIA may include, but are not limited to, headache, confusion, visual changes, dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulty. Focal neurologic deficits may also occur. Symptoms associated with ARIA usually resolve over time. In addition to ARIA, intracerebral hemorrhages greater than 1 cm in diameter have occurred in patients treated with KISUNLA.Consider the benefit of KISUNLA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and potential risk of serious adverse events associated with ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with KISUNLA.

Study 1 and Study 2 Overview[see Clinical Studies ]In Study 1, safety was assessed in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 1 (n = 853) compared to those who received placebo (n = 874). In Study 2, the effect of different dosing regimens of KISUNLA on ARIA was assessed, including in patients who received KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=212), which is the recommended dosage and described below.Incidence of ARIAA lower incidence of ARIA was observed with Dosing Regimen 2 as compared to Dosing Regimen 1. Therefore, Dosing Regimen 2 is the recommended dosage for KISUNLA.In Study 1, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 6% of patients through 18 months of treatment with KISUNLA[see Adverse Reactions ]. Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 85% of those patients. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 36%, 24%, and 31% of patients treated with KISUNLA, respectively, compared to 14%, 2%, and 13% of patients on placebo, respectively. There was no increase in isolated ARIA-H (i.e., ARIA-H in patients who did not also experience ARIA-E) for KISUNLA compared to placebo.In Study 2, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 3% of patients and symptomatic ARIA-H occurred in less than 1% of patients through 12 months of treatment with KISUNLA[see Adverse Reactions ]. Clinical symptoms associated with ARIA-E resolved in approximately 67% of patients at 12 months. Including asymptomatic radiographic events, ARIA, ARIA-E, and ARIA-H were observed in 29%, 16%, and 25% of patients treated with KISUNLA.Incidence of Intracerebral HemorrhageIntracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was reported in 0.5% of patients treated with KISUNLA compared to 0.2% of patients on placebo in Study 1, and in 1% of patients treated with KISUNLA in Study 2. Fatal events of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking KISUNLA have been observed.Risk Factors for ARIA and Intracerebral HemorrhageApoE ε4 Carrier StatusThe risk of ARIA, including symptomatic and serious ARIA, is increased in apolipoprotein E ε4 (ApoE ε4) homozygotes, which include approximately 15% of Alzheimer's disease patients.In Study 1, of patients in the KISUNLA arm (n=850), 17% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 53% were heterozygotes, and 30% were noncarriers. The incidence of ARIA through 18 months was higher in ApoE ε4 homozygotes (55% on KISUNLA vs. 22% on placebo) than in heterozygotes (36% on KISUNLA vs. 13% on placebo) and noncarriers (25% on KISUNLA vs. 12% on placebo). Among patients treated with KISUNLA, symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 8% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 7% of heterozygotes and 4% of noncarriers. Serious events of ARIA occurred in 3% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 2% of heterozygotes, and 1% of noncarriers.In Study 2, of patients treated with KISUNLA Dosing Regimen 2 (n=211), 10% were ApoE ε4 homozygotes, 55% were heterozygotes, and 36% were noncarriers. Symptomatic ARIA-E occurred in 0% of ApoE ε4 homozygotes compared with 4% of heterozygotes and 3% of noncarriers. The small number of events and limited exposure in the ApoE ε4 subgroups limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA-E.The recommendations for management of ARIA do not differ based on ApoE ε4 carrier status

[see Dosage and Administration ]. Testing for ApoE ε4 status should be performed prior to initiation of treatment to inform the risk of developing ARIA. Prior to testing, prescribers should discuss with patients the risk of ARIA across genotypes and the implications of genetic testing results. Prescribers should inform patients that if genotype testing is not performed, they can still be treated with KISUNLA; however, it cannot be determined if they are ApoE ε4 homozygotes and at a higher risk for ARIA. An FDA-authorized test for detection of ApoE ε4 alleles to identify patients at risk of ARIA if treated with KISUNLA is not currently available. Currently available tests used to identify ApoE ε4 alleles may vary in accuracy and design.Radiographic Findings of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)Neuroimaging findings that may indicate CAA include evidence of prior intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microhemorrhage, and cortical superficial siderosis. CAA has an increased risk for intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of an ApoE ε4 allele is also associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

In Study 1, the baseline presence of at least 2 microhemorrhages or the presence of at least 1 area of superficial siderosis on MRI, which may be suggestive of CAA, were identified as risk factors for ARIA. Patients were excluded from enrollment in Study 1 for findings on neuroimaging of prior intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter, more than 4 microhemorrhages, more than 1 area of superficial siderosis, severe white matter disease, and vasogenic edema.

Concomitant Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic MedicationIn Study 1, baseline use of antithrombotic medication (aspirin, other antiplatelets, or anticoagulants) was allowed. The majority of exposures to antithrombotic medications were to aspirin. The incidence of ARIA-H was 30% (106/349) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication within 30 days compared to 29% (148/504) who did not receive an antithrombotic within 30 days of an ARIA-H event. The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage greater than 1 cm in diameter was 0.6% (2/349 patients) in patients taking KISUNLA with a concomitant antithrombotic medication compared to 0.4% (2/504) in those who did not receive an antithrombotic. The number of events and the limited exposure to non-aspirin antithrombotic medications limit definitive conclusions about the risk of ARIA or intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic medications.